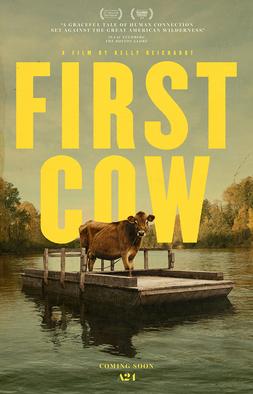

FIRST COW ***1/2

Kelly Reichardt

2019

IDEA: In 1820s Oregon Territory, a fur trapper befriends a Chinese immigrant, and together start a baking business using a cow shipped to the area from France.

BLURB: In the damp evergreens, muds, and ochres of an untamed Pacific Northwest, First Cow stages a microcosm of America in its incipient progress: toward industrialism and capitalism, and the social and material realities upon which they operate. Reichardt’s opening image of a cargo ship crawling across an Oregon river casts the historical events of the film as a direct prelude to these organizing systems of global contemporary life, effectively transforming even the most unassuming moments into harbingers of a faraway modernity. Yet Reichardt and screenwriter Jonathan Raymond are not didactic about these signals; by meticulously but only partially parceling out details of character and milieu, they create an immersive, in-the-moment portrait of the early American West that feels appropriately inchoate, filled with itinerant pursuits and narratives in media res. Supported by Christopher Blauvelt’s earthy lensing, First Cow is so impressive largely because of the authenticity this approach confers, making palpable a world not yet fully molded to the image of commerce, whose opportunities have been only provisionally tapped. It’s also impressive because Reichardt and Raymond refuse to view this fledgling American project in popular dualistic terms. If they’re somberly aware of the country’s founding and proliferating principles of exploitation and inequality, they’re also eager to celebrate the multiethnic relations that make up its cultural bedrock. First Cow is characterized by the poignant ambivalence that arises from this measured perspective: from the understanding that a cow’s milk can be both a gift of a nature and a privatized commodity.